'Crime and Punishment' by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Tuesday, September 11, 2018

Edit

Raskolnikov, an impoverished student living in the St. Petersburg of the tsars, is determined to overreach his humanity and assert his untrammeled individual will. When he commits an act of murder and theft, he sets into motion a story that, for its excruciating suspense, its atmospheric vividness, and its depth of characterization and vision is almost unequaled in the literatures of the world. The best known of Dostoevsky’s masterpieces, Crime and Punishment can bear any amount of rereading without losing a drop of its power over our imaginations.

Dostoevsky’s drama of sin, guilt, and redemption transforms the sordid story of an old woman’s murder into the nineteenth century’s profoundest and most compelling philosophical novel.

MY THOUGHTS:

This is my choice for the Crime Classic category of the 2018 Back to the Classics challenge, and what could be better? I enjoyed The Brothers Karamazov, and psyched myself up for more Dostoevsky.

The title sounds reminiscent of Jane Austen but with a grim twist. That matches the hero, who's a prototype emo kid from the nineteenth century. Rodian Romanovich Raskolnikov is an impoverished Uni drop-out living (or existing) in St Petersburg. He's stand-offish, proud and resists the sympathy of his family and best friend, who all keep loving him anyway. He's perfected his, 'Leave me alone, I'm tired,' line, and even in his good moods, he's like a tinder box everyone is nervous about sparking off. He even looks the part, with his pallid complexion, and dark hair and eyes. But we're told from the start that he's devastatingly handsome.

He has his creepy smile down pat too. It popped up so often, I started making a list. To mention just a few occasions, he gives a distorted smile, a poisonous smile, a thin, ironic smile, a cold and casual smile, an odd, self-disparaging smile, and a vacant smile. He also has a silent, caustic smile, a hate-filled, supercilious smile and a malevolent smile. To cap it all off is his lost and ugly smile. The only sort never forthcoming is a friendly and open smile. So that's our guy, now on with his story.

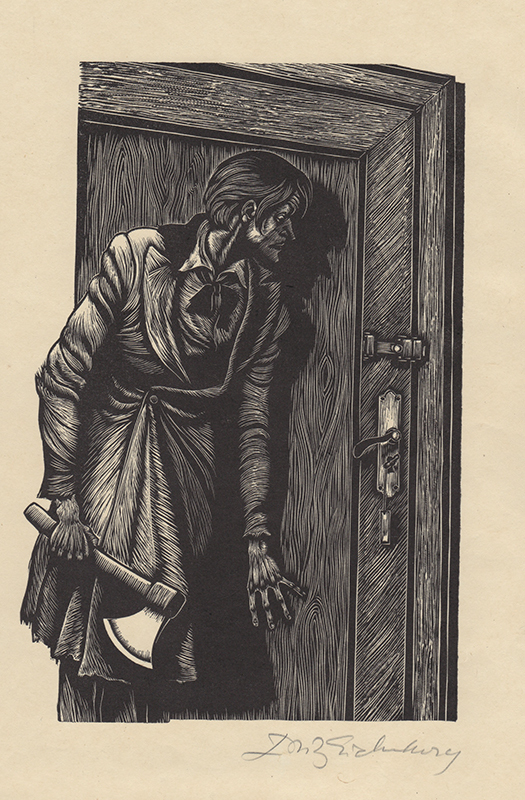

Raskolnikov's redeeming characteristic is his concern for underdogs who can't defend themselves. But he has too much time on his hands and over-thinks way too much. He devises a terrible plan, which he forces to fit his personal ideology. Not far from him lives a mean old female pawnbroker named Alyona Ivanovna, who Raskolnikov perceives as the embodiment of everything wrong with the world. She preys on the poor and beats her feeble-minded sister. Since she's a louse in his opinion, he decides to kill her, then use her money to help the poor. He hopes to become a folk-hero like Napoleon, a person who the normal restraints of the law no longer apply to. He reasons that he'll be doing the world a favour when he exterminates Alyona. We go along with him for the ride, as he commits the crime and deals with the aftermath, which begins immediately, when her sister unexpectedly walks in.

Raskolnikov's redeeming characteristic is his concern for underdogs who can't defend themselves. But he has too much time on his hands and over-thinks way too much. He devises a terrible plan, which he forces to fit his personal ideology. Not far from him lives a mean old female pawnbroker named Alyona Ivanovna, who Raskolnikov perceives as the embodiment of everything wrong with the world. She preys on the poor and beats her feeble-minded sister. Since she's a louse in his opinion, he decides to kill her, then use her money to help the poor. He hopes to become a folk-hero like Napoleon, a person who the normal restraints of the law no longer apply to. He reasons that he'll be doing the world a favour when he exterminates Alyona. We go along with him for the ride, as he commits the crime and deals with the aftermath, which begins immediately, when her sister unexpectedly walks in.Raskolnikov takes an interest in a girl named Sonya Marmelodov, with clear, quiet eyes, because he sees in her a like mind. Sonya is willing to sacrifice her good name for the sake of others, by resorting to prostitution to help feed her starving family. In the same way, he reasons he's become a murderer to help release the world from tyranny. She's appalled like us when she hears his analogy, but by then she's fallen for that emo charm and handsome face. So there's a romantic thread running through the book too. Sonya has a heart of gold, and some readers might think she deserves better than Raskolnikov, but since he's what she really wants, I guess you can say she earns her reward, even though an axe-murderer wouldn't be every girl's dream man.

Dostoevsky might be hinting that we need a good, sound anchor for our thoughts, especially if they tend to veer on the intense side, and run all over the place. On the last few pages, Raskolnikov starts reading the New Testament, because he respects the kind and awesome person it helped shape Sonya into. So we would hope that it might help set some boundaries and parameters for his genuine, seeking heart. Yet it makes me sad to see that even well into his sentence in Siberia, he still doesn't repent of his crime, and defends his reasons for murdering Alyona. I wonder how often this story might have sparked anything dark in other readers, who took Raskolnikov's reasoning on board and said, 'Heck yeah, I can commit murder and justify it by becoming a philanthropist.' How many readers agree with him that some types of murder should be regarded as more acceptable than others? Or is assuming the right to decide whose life is worthwhile a heinous cheek, however you choose to look at it?

One main theme might be not to get carried away thinking you're anything special, because when you imagine you're different from everyone else, you probably aren't. Raskolnikov learns this in retrospect. I doubt he's even an exceptional baddie, as many terrorists throughout the years have probably shared his train of thought. When we start regarding somebody as a symbol instead of a human being, we get into very murky waters and become dangerous. ('It wasn't a person, but a principle I killed.') Some might see him as a tragic hero, but I'll always think of him as the wiry 23-year-old male who murders a defenseless old lady in her own home. Since he's so passionate about being generous and defending the weak, there's a stinking irony there. If he really wanted to be a people's hero, why not choose a more threatening figure who might have a chance of fighting back?

One main theme might be not to get carried away thinking you're anything special, because when you imagine you're different from everyone else, you probably aren't. Raskolnikov learns this in retrospect. I doubt he's even an exceptional baddie, as many terrorists throughout the years have probably shared his train of thought. When we start regarding somebody as a symbol instead of a human being, we get into very murky waters and become dangerous. ('It wasn't a person, but a principle I killed.') Some might see him as a tragic hero, but I'll always think of him as the wiry 23-year-old male who murders a defenseless old lady in her own home. Since he's so passionate about being generous and defending the weak, there's a stinking irony there. If he really wanted to be a people's hero, why not choose a more threatening figure who might have a chance of fighting back?Other characters give us occasional relief from Raskolnikov's head space. There's his doting mother and his sister Dunya, who seems to attract sleazy middle-aged suitors like moths to a flame. Most lovable and loyal of all is his best friend Razumikhin, who has no idea what Raskolnikov has been up to. Razumikhin is cheerful, kind and talkative with some great lines, such as, 'Talking nonsense is the sole privilege mankind possesses over the other organisms. It's by talking nonsense one gets to the truth. Not one truth has been derived at without people first having talked a dozen reams of nonsense.' And after all his friend puts him through, his final verdict is, 'The fact is, that in spite of it all, you're really an excellent chap.'

I'm not sure I completely agree with Razumikhin, but the story kept me turning pages, and had me reflecting that it's all too easy for modern westerners to sit back and judge people who are physically, spiritually and emotionally destitute. Who can say what we'd be driven to do under similar circumstances to these characters? It's a stark, oppressive novel in many ways, yet offers glimpses of optimism. The head of investigation, Porfiry Petrovich (quite a cool character) tells Raskolnikov, 'I know you don't believe it, but I promise you, life will carry you through. You'll even get to like each other afterwards.' Maybe that's what we should all take on board. If there can be a future together for an axe-murderer and a prostitute, I guess there's hope for any of us to shed our perceived labels.

🌟🌟🌟🌟

If you're interested in more, he's also on my list of characters who contemplate murder.